Amazon System Design

Electronics to clothes to personal care to medicines, we are buying everything online these days! Even grocery shopping happens on Amazon these days! But how do you build a system that sells such a wide variety of products, provides smooth checkout options, and doesn’t crash during huge sales like The Black Friday Sale and The Great Indian Festival? Well, let’s have a look.

So as always, we will start by locking down the requirements.

Functional Requirements

- Should provide a search functionality with delivery ETA

- Should provide a catalog of all products

- Should provide Cart and Wishlist features

- Should handle payment flow smoothly

- Should provide a view for all previous orders

Non Functional Requirements

- Low latency

- High availability

- High consistency

Now for a system that handles such high traffic, especially during huge sales, meeting all three non-functional requirements might be difficult. But not everything needs to be always available, have low latency, and be extremely consistent. For example, payment and inventory systems should be highly consistent even at the cost of availability, Search needs to be highly available even if it is slightly inconsistent. Most user-facing components should have a low enough latency.

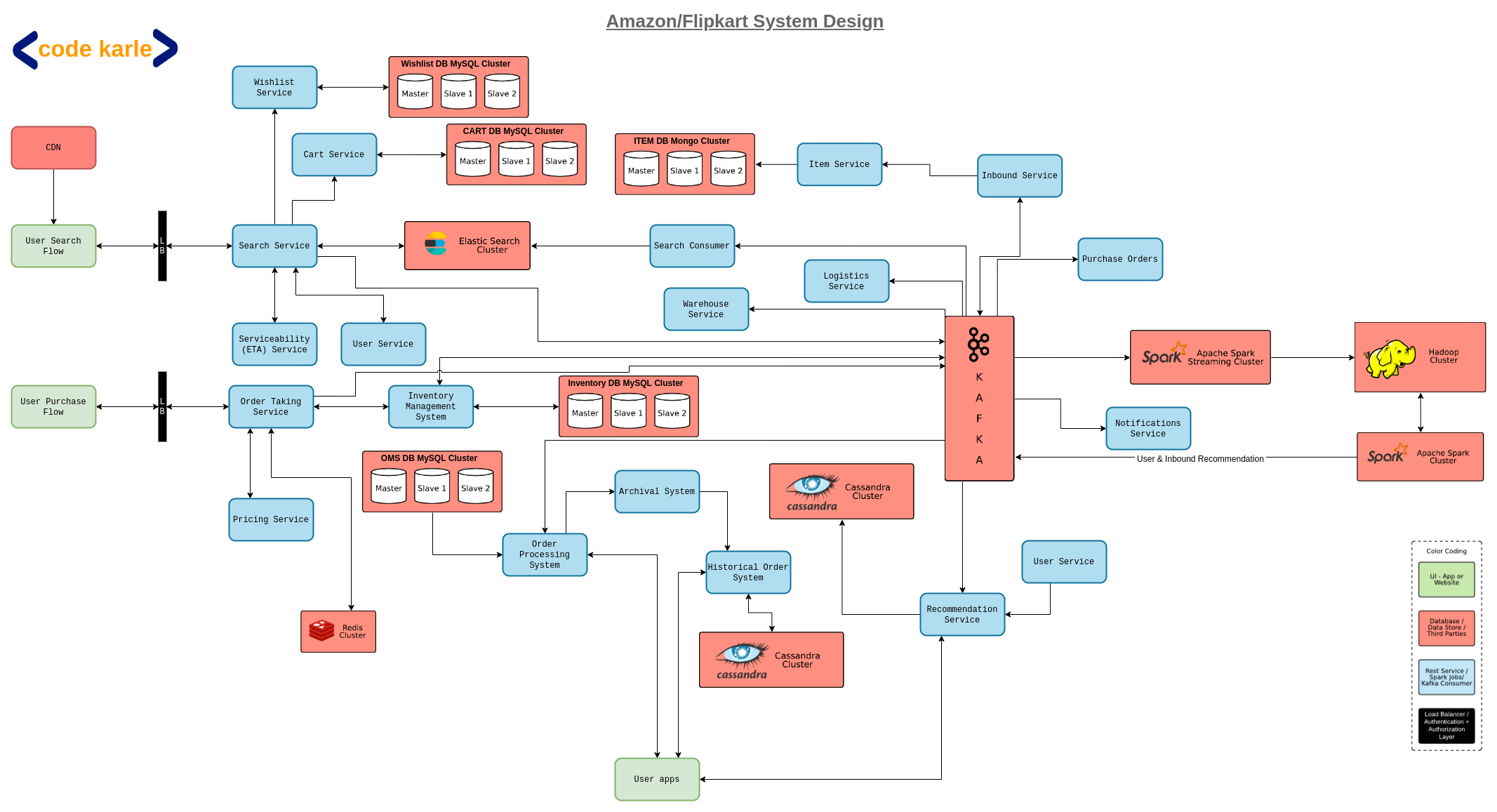

Now that we have clear requirements, let’s start building the system. To keep things simple we will divide the system into two flows - Home/Search view and Purchase/Checkout flow.

Home and Search Flow

There will be two UIs that we will offer, a home screen which will have some recommendations, personalized or general depending on if it is a returning user or a new user, and a search page where users can see results based on some search text.

Now, a company operating at a scale like Amazon’s will be interacting with multiple suppliers. To manage these suppliers we will need multiple services that we are collectively calling Inbound Services. These inbound services will interact with supplier systems and fetch the relevant data. When a new supplier is added or a supplier adds a new item to their inventory, it needs to flow into the system so that this information is easily available to the user. This information, again, will enter our system through the inbound service and reach the user on the homepage or through search results through various consumers listening to a Kafka which will receive events from Inbound services anytime such changes happen. Let’s look at these consumers in a little more detail.

One of the consumers in our system is an Item service that will listen to Kafka to onboard new items and will expose APIs to add, update, and fetch items. It sits on a MongoDB because this item related data will be unstructured. Unstructured in the sense that various types of items will have different attributes. For example, a shirt will have size, fabric, and color attributes, whereas a TV would have attributes like screen size, color technology, weight, resolution, etc.

As soon as a new item is on-boarded, a search consumer will make sure that this item can be queried by the users. It will read and process all the new items being on-boarded and format it such that they can be stored into the database and the search system can understand it. After formatting, the search consumer will put this data in an ElasticSearch database. We use an ElasticSearch here as it is very efficient for text-based search and also supports fuzzy search which we need for seamless user experience. Which have discussed this in more detail in another tutorial where we go over which databases might be best for what scenarios.

Now a Search Service interacting with this ElasticSearch will expose APIs to filter, sort, search, etc the products. If you remember, in the functional requirements we mentioned ‘search with delivery ETA’. This can be extended to the requirement that we should not show the search results that cannot be delivered to the user as that would be a poor user experience. For this, the search service will talk to something called Serviceability and TAT service. Serviceability and TAT service will check which warehouse the product will be delivered from, if there is a route between the warehouse and the user’s pin code, if yes then can that route be used to carry this product. It will also figure out an approximate delivery date and communicate all this information to the search service. The search service will further communicate this information to the user.

From the search screen, the user should be able to wishlist a product or add it to the cart. This happens via Wishlist Service and Cart Service . Wishlist service is a repo of all wish lists in our system and cart service is a repo of all carts. Both these services will be built in the exactly same way in that they each provide APIs to fetch, update, add to and delete items from a Wishlist or cart, and they will both sit on MySQL DBs. They can be built on the same hardware but considering that wishlists tend to be very long, especially when a sale might be approaching, it is suggested to have separate hardware for these services. This way scaling the hardware for individual service becomes much easier.

Now, each time a search happens, an event is fed to Kafka. This helps us build a recommendation system personalized to the user’s interests and also a general recommendation based on the most popular products. Similarly, Wishlist and cart services will also send similar events to Kafka. Let us have a look at how this analytics part of the system will work in detail.

Our Kafka service will be connected to a spark streaming consumer which will generate real-time reports like which are the most sought after products in the last hour or day, most wishlisted item, locations from where most orders are coming, highest revenue-generating categories, etc. All this data coming from Kafka will also be dumped in a Hadoop cluster on which some standard algorithms like ALS can be run to identify the next set of products a user might need to buy based on their past purchases, based on which we can generate personalized recommendations for them. It will also tell us about the products other similar users have searched, wishlisted, or bought, which we can add to the recommendations for this user. Once we have these recommendations, a spark cluster will talk to a recommendation service, which is a repo of all recommendations in our system, whether they are general recommendations against a user id, or based on a category of products. This way the users will see general recommendations on their homepage but if they are going through a certain category of products the recommendations will be filtered out.

The next component is the User Service. It is a repo of all users and also provides APIs to fetch, update, add, and delete users from our system. It sits on a MySQL database and maintains a Redis cache. So let’s say our search service wants to fetch a user’s pin code to communicate to the serviceability service, user service will first check in the Redis, if Redis doesn’t have the information it will lookup in the MySQL database, get the user’s information, store it in Redis for further use and return it to the search service.

Now, remember we mentioned Serviceability + TAT service, which identifies whether or not we deliver to a location, and calculates the ETA? It does so with the help of Logistic Service and Warehouse Service. Serviceability service can access warehouse service to get a repo of all products stored in a warehouse, or it can talk to logistic service to find out all the courier partners, or to fetch a list of pin codes that we can service, etc. Based on all this information, serviceability and TAT service will come up with the shortest route between the warehouse housing the product and the user and will also compute the ETA for delivery. How this calculation happens is discussed in detail in the Google Maps tutorial if you want a detailed explanation. Now, an important thing to remember here is that none of these calculations will happen at runtime. Everything will be pre-computed and cached so that we can instantaneously give an ETA to the users

Now we have discussed how users can search products, how supplier inventory is synced with our system, how we generate recommendations, even how we find out ETA after the order has been placed. But HOW will the order be placed?

Purchase and Checkout flow

When a user wants to place an order, the request will go to an Order taking service, which is a part of the larger order management system. The order management system sits on a MySQL database. As expected we have multiple tables like customer table, item table, order table, etc, and a lot of transactions going on across these tables. Now we don’t want two users to be able to order the last piece of the latest AirPods in our warehouse, just because our database couldn’t reflect the change promptly enough. This means we need ACID properties of relational databases, hence MySQL.

Now as soon as the order taking service is called, a record will be created in a Redis with an order id, date, and time at which the order was created and an expiry time for the order id. Along with these details, there will also be a status against that order id, let’s say initially this status will be “created”. Now the next step will be to call the inventory service. For instance, there were 5 sets of Sony 65” Smart TV in stock before the order was created. After placing the order the inventory count for the product will be reduced to 4, only after this the user will be redirected to payments. But why do we update the inventory BEFORE the payment is completed? What if instead of 5 TVs, we only had one in stock and 3 people trying to buy it? If we reduce the inventory count before going to the payment flow, 2 out of the 3 buyers will see that the item is already out of stock, and their flow will end before even going to the payments page. This can be implemented easily enough by keeping a constraint on the inventory count such that if the count goes negative you shouldn’t be able to place the order.

Now, once the inventory is successfully updated, the order taking service will talk to the payments service, which will talk to the payment gateway and carry out the whole payment flow. Now there can be three possible outcomes from this payment flow - success response, failure response, and no response. Let’s start with the happy flow. Say order O1 was placed at 10:01 with expiry time as 10:05 and at 10:03 we got payment success response. In this case, we will update the order status to “placed” and an event will be fired to Kafka saying that an order is placed against this product with so and so order details. What would have happened if the payment had failed? Now, remember before starting the payment flow we have already updated the inventory. This means as far as the inventory system is concerned the order has already been placed, and now that the payment has failed, we need to cancel this order. This means the order status will be updated to “canceled”. Since the order is canceled we need to revert the count in the inventory database, so we will again talk to the inventory service. On top of this order taking system and inventory system, we will have a reconciliation system that ensures that orders count and inventory count are in sync and not inconsistent with each other.

Now suppose the user started the payment flow but without completing the payment closed the browser. In this case, there will be no response from the payment service. That means we still have the Sony 65” Smart TV in our stock but it isn’t reflected in our inventory system. Now, this is where the Redis comes in. At 10:05 the Redis record for O1 will get expired and will implement an expiry callback. At this point, the order taking service will talk to the payment service to time out the payment and mark it as failed. From here out the flow will be the same as that in case of a failed payment case, the order will be canceled and inventory count will be rolled back.

Now there is a potential race condition here. What if the payment success and order expiry happens around the same time? The most common case would be payment success followed by order id expiry. In this case, to skip the expiry event, we can delete the record from Redis as soon as the payment success response is received. A problematic case would be if payment success followed the expiry event. Our order expires at 10:05, say payment success comes in at 10:07, but by then the order will already be canceled. So we can either refund the money to the customer and let them know that due to some reason their order cannot be placed or we can place the order from our end, mark the parent as complete and update the status to “placed”.

Now, as soon as we get the response from the payment system we will put an event in Kafka. Suppose we just sold the last Sony 65” Smart TV, to make sure no users try to order it we should remove it from the search results i.e. as soon as an item goes out of stock, search consumers will remove the item from the search listing. Now our system is pretty consistent, does not show products that cannot or should not be ordered, handles the payment flow smoothly, supports search, provides personalized recommendations, etc. But can we optimize it further?

Well, there is a bottleneck in our system and that is the MySQL database used in the order management system. A company like Amazon will receive millions of requests every day and orders data will be saved for at least a few years for audit purposes. This means the order management system database will be MASSIVE. But we need ACID properties to maintain consistency, that was the whole point of using MySQL. But do we need to keep even the delivered or canceled orders in MySQL? They are already in the terminal state and will not affect other orders. So when an order reaches a terminal state like delivered or canceled, we will move it out to a Cassandra and this will be implemented with the help of order processing service and historical order service. These services are again a part of the larger order management system. Order processing service will take care of the order lifecycle i.e. whatever changes happen to the order after placing, like fetching order details for tracking or fetching orders by status, etc will go through this service. Historical order service will provide APIs to fetch details of delivered or canceled orders. An archival service will query the order processing service to fetch all orders with terminal status and then talk to historical service to insert them in Cassandra. Once this Cassandra write is done it will again talk to the order processing service to delete these completed orders from the MySQL database. But why Cassandra?

The thing about the orders database is that even though the data is massive, there will be a fixed variety of queries that we will run on it like fetching orders by id or status or created date or category, etc I.e. large data with finite queries. This is the perfect use case for Cassandra. We have an article about how to choose the right database for our requirements, where we have discussed this in more detail. You can check it out if interested.

Now that the users can successfully place their orders in our system, they might want to see their past orders as well. This is where the Orders View comes in. There will be an intermediate service that will talk to the order processing service and historical service to fetch all ongoing as well as completed orders and communicate to the orders view.

Also, whenever an order is placed or the status changes to “in transit” or “delivered”, either the seller or the customer needs to be notified. This happens through the notification service, which we have discussed in our Notification Service tutorial. Again, every step of the way Kafka will continuously get events. Through the spark streaming services, we will get simpler real-time reports, at the same time all the data, as discussed previously, will be dumped into a Hadoop cluster. This Hadoop cluster will run some more specific algorithms to generate personalized recommendations that will be stored in the recommendation service we discussed in the previous sections.

That should be it for Amazon System Design! Send in your thoughts on our youtube video!