WhatsApp System Design

I don’t think anybody goes a day without using WhatsApp anymore. WhatsApp is easily one of the most used mobile applications out there. And why not, it is connecting people across the world in a VERY pocket friendly and convenient manner.

But how exactly does it work? Or any messenger service for that matter. In this article, we will look at a high-level system architecture for chat applications like WhatsApp and Facebook messenger. First things first, let’s define the requirements we are going to focus on.

Functional Requirements

- Should support one-on-one chats

- Should support group chats

- Should have image, video and file-sharing capabilities

- Should indicate read/receipt of messages

- Show indicate last seen time of users

Non Functional Requirements

- Should have very very low latency

- Should be always available

- There shouldn’t be any lags

- Should be highly scalable

So let’s get right to it. Let us see how messages are exchanged in a system like WhatsApp.

System Architecture

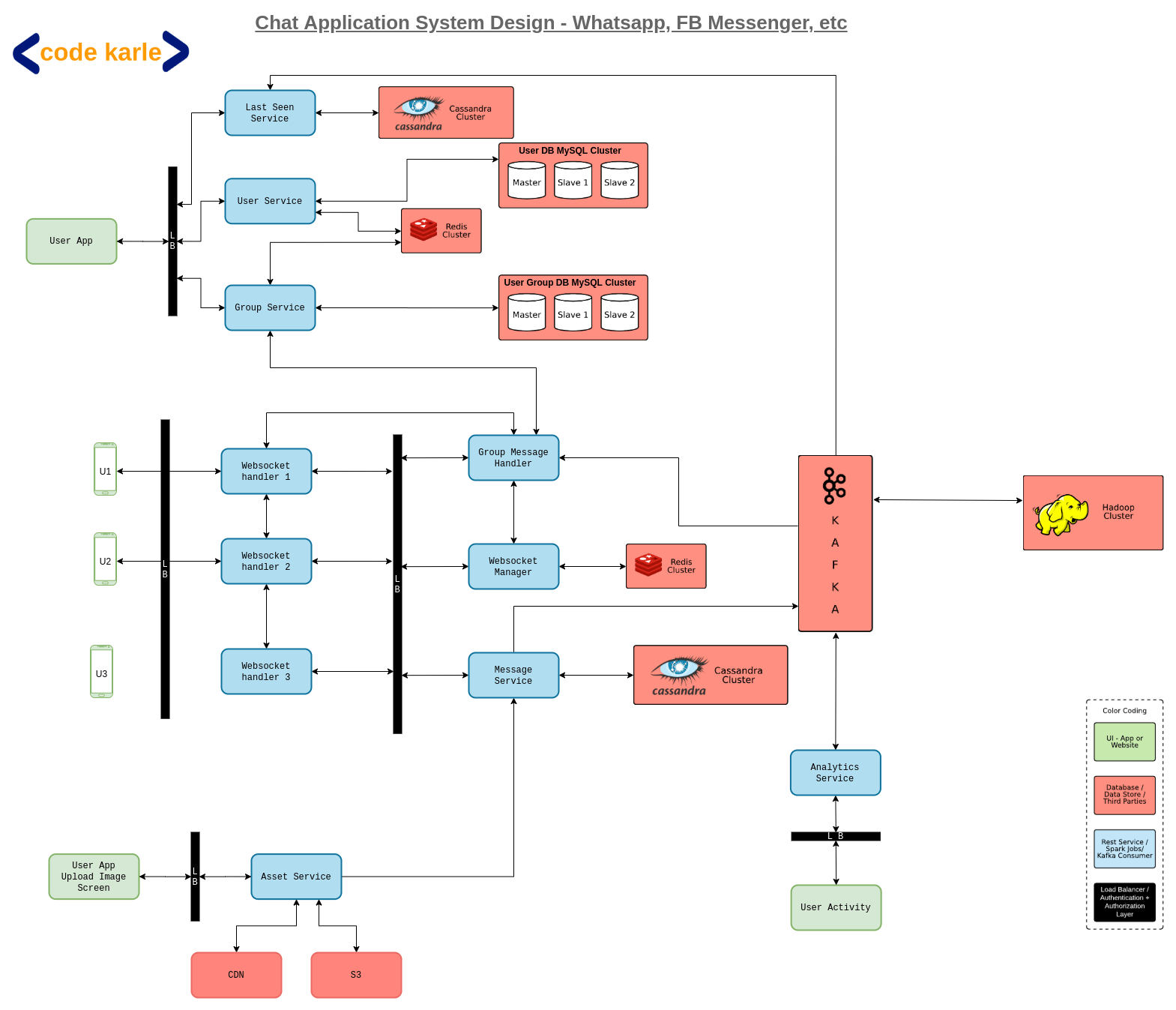

When both users are online

Let’s assume user U1 wants to send a message to user U2. Now as we can see from the flowchart, U1 is connected to a Web Socket Handler WSH1. A web socket handler is a lightweight server that will keep an open connection with all the active users. Considering the kind of scale WhatsApp and Facebook Messenger handle every day, one web socket handler is not enough to support all users, so there will be multiple web socket handlers in our system.

But how many web socket handlers do you need?

A web socket handler is, as we mentioned, a lightweight server, a machine. And each machine will have approximately 65K open ports. Even if we end up using up to 5K ports for our internal use and communicating with other services in our system, it still leaves us with up to 60K ports that we can use to connect with users. So a single machine can hold one-on-one connections with up to 60K users. Now depending on how many active users we expect to have we can come up with a reasonable number of web socket handlers we require. Another important point here is that these machines will be distributed across various geographical locations to reduce latency.

A web socket handler will be connected to a Web Socket Manager which is a repository of information about which web socket handlers are connected to which users. It sits on top of a Redis which stores two types of information:

- Which user is connected to which web socket handler

- What all users are connected to a web socket handler

When a connection between a user and web socket handler breaks and they connect to another handler, through the web socket manager this information is updated into Redis.

A Web socket handler, while talking to a web socket manager will also, in parallel, talk to a Message Service, which is a repository of all messages in the system. It will expose APIs to get messages by various filters like user id, message-id, delivery status, etc. This messaging service sits on top of Cassandra. Now we can expect that new users will keep getting added to the system every day and all users, old and new, will keep having new conversations every day i.e. message service needs to build on top of a data store that can handle ever-increasing data. And we also know that there are a finite number of queries we can run on Message service due to the finite number of APIs it exposes to web socket handlers. These requirements and query patterns fit with those that Cassandra is best suited for.

You can refer to our article about choosing the best storage solutions to get more clarity about why we are using Cassandra and Redis where we are, and what other alternatives you could think about.

Another thing to keep in mind is, there are two types of systems we could be building here. Something like Facebook Messenger, that stores all messages permanently, or something like WhatsApp that stores the messages only until they are undelivered. Once we receive confirmation that the messages are successfully received, they can be deleted from the system. This is something we need to clarify in the requirement gathering stage because we will choose the database for our message service based on this specification. Deletes are not handled very efficiently in Cassandra, so if we are building something similar to WhatsApp we might decide to go with another database. For the scope of this article though let us stick to Cassandra.

Now let us get back to the conversation U1 and U2 are having. As we can see from the architecture flow diagram, U1 is connected to the web socket handler WSH1. So when U1 decides to send a message to U2, it communicates this to WSH1. WSH1 will then talk to the web socket manager to find out which web socket handler is handling U2, and the web socket manager will respond that U2 is connected to WSH2. As we discussed previously, WSH1 will make a parallel call to Message service which will save the message into Cassandra and assign it a message id say M1. Now that WSH1 has a message id M1 and knows that U2 is connected to WSH2, it will talk to WSH2.

We already know that if a user is connected to a web socket handler, they are online. But U2 could be on the chat screen for U1, in which case M1 will be immediately delivered and seen or it might not be on U1’s chat screen in which case the message will only be delivered. Accordingly, WSH2 will communicate to the message service that U2 has received or seen the message. Now there is a possibility we don’t want to store the read/received status for the message, but we will still need to store the status for at least some time. Consider a situation where U1 sends a message to U2 and then U1 goes offline. Now U2 has received the message M1 but U1 doesn’t know about it. So the status will be stored in Cassandra against the message as delivered or seen for at least as long as it is not communicated to U1. Once U1 receives the status of the message it can be deleted if required.

While communicating to U1 that U2 had received or seen the message, WSH2 will again go through the web socket manager to find out that WSH1 is connected to U1 and then talk to WSH1. If U1 and U2 have a whole conversation with multiple messages, a large number of calls will be made to the web socket manager. To avoid this each handler will cache 2 types of information-

- Which users are connected to itself, so if U1 and U2 were both connected to the same handler, that call to the web socket manager could be avoided.

- Information about recent conversations, like which user is connected to which handler.

An important thing here is the cache time. How long does a web socket handler cache information about recent conversations? This cache time will be very low. As we mentioned earlier, web socket handlers will be distributed across the globe to reduce latency. But this also means that maybe because of connectivity issues or network traffic or other such reasons, the connection between user and web socket handler might break and the user will connect with another handler i.e. information about other web socket handlers will become outdated very frequently. And we don’t want to fill our limited cache space with outdated information, hence the short cache times.

When the recipient is offline

We have seen the flow for when both users were online. What happens when U1 tries to send a message to U3, which is offline? WSH1 talks to the web socket manager to find out which handler is connected to U3, and finds out U3 is not connected to anyone, so that part of the flow ends here. At the same time, it is also talking to the message service where the message is stored with an id, say, M2. Now when U3 comes online, let’s say it connects to WSH3, the first thing WSH3 does is to check in with message service if there are any undelivered messages for U3 and these messages will be sent to U3 via WSH3. And then WSH3 will communicate this change in status to WSH1 in the previously discussed manner.

Race condition

Yes! There is a possibility for a race condition here. Now, remember the web socket handler’s communications with web socket manager and the message service are running in parallel. Also, note that it is expected to have a slight delay while communicating with the services that a change has been made to the system. What happens when WSH1 checks with the web socket manager for U3 right when it comes online? A few things will happen here -

- Web socket manager returns that U3 is not connected to any Web socket handler

- WSH3 talks to message service to get all undelivered messages for U3.

- Web socket manager stores that WSH3 is handling U3

- M2 gets stored in Cassandra

There are ways to handle this race condition, one of the more popular methods is polling. Web socket handlers will keep polling the message service every few minutes to ensure they haven’t missed any messages.

Local Caching

Let’s say when U1 sent the message to U3 it was offline i.e. not connected to any web socket handler. In this case, the message will be stored in a local database on the device. As soon as the device gets connected to the network and a web socket handler, it will pull all the messages from the local database and send them.

Group chats

What we discussed until now was how a personal chat works on a system like WhatsApp. But what about group chats? Let’s say U1 wants to send a message to G1. Now, groups will behave a little differently from users. Web socket handlers won’t keep track of groups, it just tracks active users. So when U1 wants to send a message to G1, WSH1 gets in touch with Message service, that U1 wants to send a message to G1, and it gets stored in Cassandra as M3. Message service will now communicate with Kafka. M3 gets saved in Kafka with an instruction that it has to be sent to G1. Now Kafka will interact with something known as Group Message Handler. The group message handler listens to Kafka and sends out all group messages. There is something called Group Service which keeps track of all the members in all groups. Group message handler talks to Group service to find out all the users in G1 and follows the same process as a web socket handler and delivers the message to all users individually.

Asset delivery

Okay. Now we are sending messages to people and groups. But messages are not the only content shared on WhatsApp. What happens when people send images, files, and videos over WhatsApp?

Ideally, when content like this is sent out it will be compressed and encrypted at the device end and the encrypted content will be sent to the receiver. Even while receiving the content will be received in an encrypted format and decrypted on the device end. In this article let us just consider the compression step.

Suppose U3 is sending an image to U2. This will happen in two steps.

- U3 will upload the image to a server and get the image id

- Then it will send the image ID to U2 and U2 can search and download the image from the server.

Now as mentioned previously, Web socket handler is a lightweight server i.e. there will be no heavy logic on web socket handler. The image will be compressed on the device side and sent to an Asset Service through the Load Balancer and asset service will store the content on S3. Based on the kind of traffic S3 receives for a particular image or content, it may or may not load the content onto a CDN. Once the image is loaded in S3, the asset service will send the image id, say I1 to U3 and U3 will communicate it to U2 through web socket handlers as discussed.

Here we can perform some optimizations. For example, in case of a high profile political or sports event, a lot of people might end up sharing the same image and we might end up with multiple copies of the same image. To avoid this, before uploading an image to asset service, U3 will send a hash of the image and if the hash is already there in the asset service, the content will not be uploaded again, but the id against the same image/content will be sent to U2. I know, you must be thinking about multiple collisions? To deal with this, instead of sending just 1 hash, we will send across multiple hashes calculated via multiple algorithms. If all the hashes match, there is a fairly high chance that it is the same image and doesn’t have to be uploaded again.

Now we have discussed almost everything that you can see in the flowchart. But what is this user service? And what exactly does the group service do?

User Service stores user-related information like name, id, profile picture, preferences, etc, and usually, this is stored in MySQL database. This information is also cached in Redis.

Group Service maintains all group related information like which user belongs to which group, user ids, group ids, a time when the group was created, a time when every user was added, status, group icon, etc. This data also will be stored in a MySQL database which will have multiple slaves in different geographical locations to reduce latency. And of course cache this data in a Redis. Usually, user service and group service will first connect to Redis to find the data, only querying a MySQL DB slave in case the data is not found in Redis.

Analytics

Every action performed by the user can be used for some sort of analytics like if a person talks a lot about sports, they are sports enthusiasts and other such things. These events are sent either to an Analytics service that sends them to Kafka or in case of messages, directly to Kafka. If the event was sending an image, the analytics service will process the image and attach some tags like “sport”, “football”, “Messi” etc, and send this information to Kafka. Kafka could further be connected to Spark streaming service that either analyzes the content as it flows in or dumps it into a Hadoop cluster which can run a wide variety of queries.

Last Seen

These events will also be listened to by the Last Seen Service which keeps track of the last seen time of the user. This information could be stored in a Redis or Cassandra in the form of user id and last seen time. But in case you want to store some additional information along with the last seen time Redis might have some memory issues so Cassandra might be a better choice.

Now when we say events, there could be two types of events, the ones fired by the app and the events fired by the users.

- App events - things like when a web socket connection is created, etc. These events will not be tracked by the last seen service.

- User events - things like when the user opens or closes or does something else in the app. These events will be used to track the last seen time.

All the components we have discussed so far are horizontally scalable. We

can spin up or remove instances as and when required. Monitoring and

And that is all, we have discussed the messaging flow for personal and group chats on WhatsApp, asset sharing, some challenges and optimizations that we can perform. We discussed the complete architecture in detail, in case you have any doubts about why we used which services like Kafka, etc, have a look at our article about various storage solution, as we have explained in detail which solutions are most suitable for which scenarios and what are the other options you might look at. And do send in your thoughts on our youtube video!